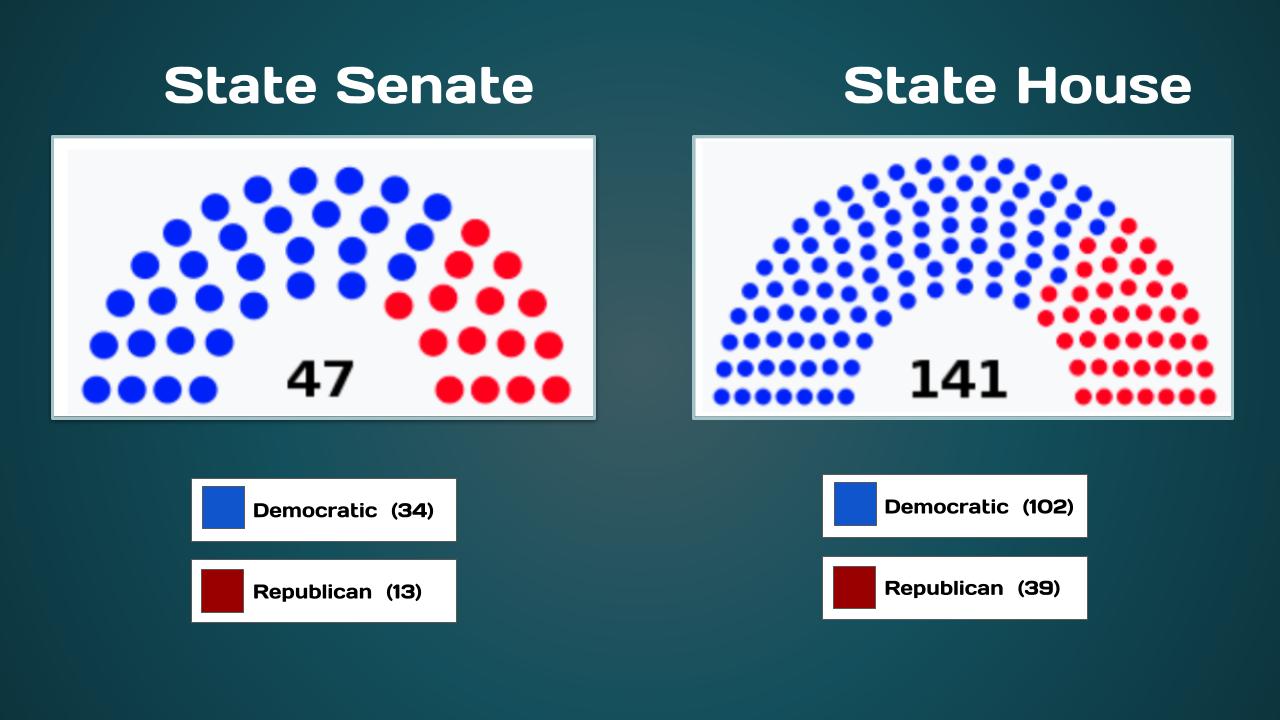

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamber, the Maryland House of Delegates, has 141 representatives. Members of both houses serve four-year terms. Each house elects its own officers, judges the qualifications and election of its own members, establishes rules for the conduct of its business, and may punish or expel its own members.

The General Assembly meets each year for 90 days to act on more than 2,300 bills including the state’s annual budget, which it must pass before adjourning sine die. The General Assembly’s 441st session convened on January 9, 2020.

Source: Wikipedia

OnAir Post: MD General Assembly