Summary

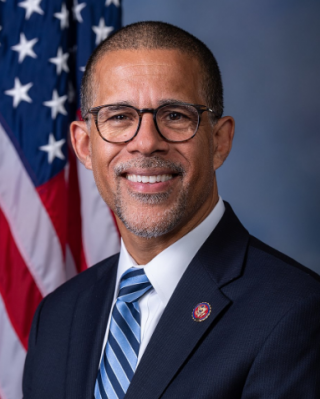

Current Position: US Representative of MD District 4 since 2017

Affiliation: Democrat

Candidate: 2023 US Senator

Former Positions: Lt. Governor; State Delegate from 1999 – 2007

Featured Quote:

USCP live in our communities in Maryland. They go into work day-in and day-out to protect our Capitol and Members of Congress, even those who put their lives in jeopardy Today, we heard their stories first hand. Their testimony should outrage and compel us to act

Featured Video:

Democratic Weekly Address — Congressman Anthony Brown

OnAir Post: Anthony Brown – MD4

News

Maryland Matters

The first U.S. stop for the nearly 2,000 Afghan interpreters and other refugees evacuated so far amid the collapse of the Afghan government has been central Virginia’s Fort Lee military base.

Tapped for its East Coast location and its ability to quickly ramp up to serve as a temporary host installation, the Army base just south of Richmond has been receiving Afghans eligible for Special Immigrant Visas since late last month.

Two other bases will soon be joining Fort Lee in processing the incoming Afghan evacuees. Department of Defense officials said Monday that they will also use Wisconsin’s Fort McCoy and Fort Bliss in Texas — which could allow for evacuating as many as 22,000 individuals to the U.S.

About

Source: Government page

Anthony Brown was elected to his first term representing Maryland’s 4th Congressional District – encompassing parts of Anne Arundel and Prince George’s Counties – on November 8, 2016 and was sworn in on January 3, 2017. He is currently serving his third term in Congress.

The son of immigrants and raised in a home where his father was the first in the family to ever attend college, Congressman Brown was taught the value of service at a young age. Through his military and public service, Anthony has devoted his life to serving his community and defending our nation.

A retired Colonel in the United States Army Reserve, Congressman Brown’s military record spanned more than a quarter century as an aviator and JAG officer, during which time he graduated first in his flight class and received both Airborne and Air Assault qualifications. Congressman Brown was awarded the Legion of Merit for his distinguished military service. In 2004, he was deployed to Iraq, where he earned a Bronze Star and became one of the nation’s highest-ranking elected officials at that time to serve a tour of duty in that conflict.

In 1998, Congressman Brown was first elected to the Maryland House of Delegates to represent Prince George’s County. Recognized by his colleagues for his leadership, Congressman Brown rose quickly, serving as Vice Chair of the powerful House Judiciary Committee and, later, as Majority Whip.

Congressman Brown made an even larger impact on Maryland during his eight years as Lt. Governor. He fought to increase investments in Maryland schools so that every child could receive a world-class education, protected victims of domestic violence, expanded health coverage to over 391,000 Marylanders, increased employment and health services to veterans, and spearheaded efforts to plan for and coordinate the arrival of 60,000 BRAC-related jobs to Maryland, including at Joint Base Andrews and Fort Meade.

Congressman Brown is a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School. He and his wife Karmen are members of St. Joseph Catholic Church in Largo. They reside in Prince George’s County where they are raising their three children, Rebecca, Jonathan, and Anthony.

Voting Record

Caucuses

Offices

Contact

Email:

Web

Government Page, Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia

Politics

Source: none

Campaign Finance

Open Secrets – We Follow the Money

Voting Record

VoteSmart – Key Votes & Ratings

Search

Wikipedia Entry

Anthony Gregory Brown (born November 21, 1961) is an American politician and lawyer serving as the attorney general of Maryland since 2023. He previously served as the U.S. representative for Maryland’s 4th congressional district from 2017 to 2023 and as the eighth lieutenant governor of Maryland from 2007 to 2015. A member of the Democratic Party, he was its nominee for governor in the 2014 election, losing to Republican Larry Hogan in a close race.

Brown served two four-year terms in the Maryland House of Delegates, representing Prince George’s County from 1999 to 2007.[1][2] He was elected to the lieutenant governorship in 2006 on the Democratic ticket with Governor Martin O’Malley; both were re-elected in 2010.[3] He is a retired colonel in the United States Army Reserve, having served in the U.S. Army for over thirty years. While lieutenant governor, Brown was the highest-ranking elected official in the nation to have served a tour of duty in Iraq.[4][5] In 2014, Brown ran unsuccessfully for the governorship, losing to Republican nominee Larry Hogan.[6] In 2016, Brown was elected to the U.S. House. His district covered most of the majority-black precincts in Prince George’s County, as well as a sliver of Anne Arundel County.[7]

In October 2021, Brown announced that he would not seek reelection to the U.S. House in 2022 and would instead run for attorney general of Maryland.[8] He won the Democratic primary on July 19, 2022. He defeated Republican lawyer Michael Peroutka in the general election on November 8, 2022, becoming Maryland’s first Black attorney general.[9]

Early life and education

Brown was born in 1961 in Huntington, New York, to immigrant parents. His father, Roy Hershel Brown, a physician, was born in Cayo Mambi, Cuba; was raised in Kingston, Jamaica; and later came to the U.S. to attend Fordham University.[10] Roy received his medical degree in Zürich, Switzerland, where he also met his future wife, Lilly I. Berlinger.[11] The couple married and Lilly moved with Brown to New York, where they had Anthony, his sister, and three brothers.[12]

The family lived in Huntington, New York, in Suffolk County on Long Island, where Anthony attended public schools, graduating from Huntington High School in 1979. In his senior year, Brown became the first African American to be elected president of Huntington High School’s student council.[13] After high school, Brown started at the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he had an appointment. He quickly switched to Harvard College, where he majored in government and resided in Quincy House.[14] At Harvard, Brown served on the Student Advisory Committee at Harvard Kennedy School‘s Institute of Politics. Since Harvard did not offer ROTC at the time, in his second year, Brown enrolled in the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps program at MIT and earned a two-year scholarship.[1] In 1984, Brown graduated with an A.B. cum laude, and as a Distinguished Military Graduate.

Military career

Upon graduation, Brown received a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. He served on active duty for five years. He graduated first in his flight class at Fort Rucker, Alabama, and received his aeronautical rating as an Army aviator. He also completed airborne training, receiving both the Basic Parachutist Badge and the Air Assault Badge. During his time on active duty, Brown served as a helicopter pilot with the Aviation Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division in Europe.[15] During that period of active duty, Brown held positions as platoon leader for a target acquisition, reconnaissance and surveillance platoon, executive officer of a general support aviation company, a battalion logistics officer, and the flight operations officer for Task Force 23.[citation needed]

Law school and legal career

After completing his active duty service, Brown returned to graduate school, entering Harvard Law School in 1989 and earning his JD degree. He attended Harvard Law School at the same time as future President Barack Obama, Artur Davis and actor Hill Harper. Brown was a member of the Board of Student Advisers. His third-year paper, written under the supervision of Professor Charles Ogletree, analyzed the scope of the Fourth Amendment‘s protections against unreasonable search and seizure in the military. Brown was chair of the Membership Committee of the Black Law Students Association.[citation needed] Brown graduated from Harvard Law, with a Juris Doctor in 1992.

After graduating from law school, Brown completed a two-year clerkship for Chief Judge Eugene Sullivan of the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. In 1994, he joined the Washington, D.C. office of the international law firm of Wilmer Cutler Pickering (now WilmerHale). Brown practiced law with the late John Payton,[16] a renowned civil rights attorney and former president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Stephen H. Sachs, who was the United States Attorney for the District of Maryland from 1967 to 1970 and was the 40th Attorney General of Maryland. In 1998, Brown received Wilmer’s Pro Bono Publico Award for his work in representing indigent clients. In 1999, Brown worked for Merrill Lynch for five months.[17] Brown joined the Prince George’s County land use and zoning law firm Gibbs & Haller in 2000, after having been elected to the Maryland General Assembly.[citation needed]

JAG Corps

Brown continued his military service transferring from the Army’s Aviation Branch to the Judge Advocate General’s Corps as a Judge Advocate General (JAG) in the United States Army Reserve. Brown began his service as a JAG with attending the JAG School at the University of Virginia and then the 10th LSO in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, where he held numerous assignments, including in the areas of international law and claims law.[citation needed] Brown ultimately attained the rank of colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve before reaching the point of mandatory retirement for a colonel with 30 years of commissioned service in July 2014.[18]

His assignments included commander of the 153rd Legal Support Organization in Norristown, Pennsylvania, where, in addition to supporting deploying service members and their families with legal services, he mobilized eighteen soldiers to Fort Hood, Texas, in support of the III Corps’ Operation New Dawn mission to Iraq. Prior to his tenure with the 153rd LSO, Brown was the staff judge advocate for the 353rd Civil Affairs Command headquartered at Fort Wadsworth, New York.

In 2004, Brown, then a member of the Maryland House of Delegates, was deployed to Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Brown served in Baghdad, Fallujah, Kirkuk, and Basra with the 353rd Civil Affairs Command as senior consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Displacement and Migration. Brown received the Bronze Star for his distinguished service in Iraq.

Maryland House of Delegates

Brown’s political career began in 1998, when he was elected to serve in the Maryland House of Delegates, representing the 25th district in Prince George’s County. Brown ran on a Democratic Party ticket with Senator Ulysses Currie, Delegate Dereck Davis, and Delegate Melony Griffith. He served two terms in the Maryland House of Delegates and rose to several positions of leadership. During his first term, Brown served on the House Economic Matters Committee. He was appointed vice chair of the Judiciary Committee in 2003. In 2004, Speaker of the House Michael E. Busch appointed Brown to the position of majority whip, the fourth-ranking position in the House.

Lieutenant governor of Maryland

In 2006, Brown was elected lieutenant governor on a ticket with Martin O’Malley, the former mayor of Baltimore.[19] The pair were the only challenging candidates to defeat an incumbent gubernatorial ticket in the 2006 election cycle.[20] On January 17, 2007, Brown was sworn in as Maryland’s 8th lieutenant governor. Both Brown and O’Malley were reelected by a 56% to 42% margin on November 2, 2010. Brown was the first person elected lieutenant governor directly from the Maryland House of Delegates.

Governor O’Malley tasked Brown to lead the O’Malley-Brown administration’s efforts on several policy fronts, including efforts to expand and improve health care, support economic development, help victims of domestic violence, increase access to higher education, and provide veterans with better services and resources.

In July 2010, Brown was elected chair of the National Lieutenant Governors Association,[21] a position he served in for a term of one year.[22]

Health care

As co-chair of the Maryland Health Care Reform Coordinating Council and Maryland’s Health Quality and Cost Council, Lt. Governor Brown led the O’Malley-Brown administration’s efforts to reduce costs, expand access, and improve the quality of care for all residents of the state. In June 2012, Brown was named “Maryland’s Public Health Hero” by the Maryland Health Care for All! Coalition.[23] He assisted in the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which according to a “non-partisan” 2012 study using Obama administration numbers and various state agency projections, would save Maryland $672 million by 2020.[24][25] In both 2011 and 2012, Brown led legislation through the Maryland General Assembly to create a health insurance exchange.[26]

Brown was severely criticized for his leadership of the development of the health insurance exchange.[27] As of April 14, 2014, it had enrolled only 66,203 individuals (including family members on shared plans).[28] The O’Malley administration apologized for the “botched” launch of the web site and had to seek emergency funding legislation to make stopgap changes to the site.[29] The state paid a contractor $125.5 million to develop and operate the failed site.[30] Due to the failed rollout, the state incurred an estimated $30.5 million in unnecessary Medicaid spending.[31] The web site failure was the subject of a federal investigation into the costs associated with developing the exchange and the site’s performance failures.[32] The state announced that it was considering scrapping its failed online health exchange altogether and hiring a new contractor to build a new online exchange using technology employed by the state of Connecticut, at an expected cost of tens of millions of dollars.[30] The Obama administration relaxed rules for residents of states like Maryland with dysfunctional online health care exchanges, allowing consumers to bypass the exchanges altogether to buy health insurance.[33]

Brown led efforts to address health disparities among racial and ethnic groups in Maryland. In 2012, he developed created Health Enterprise Zones,[34] which would use incentives to increase the number of primary care providers and other essential health care services in underserved communities. The goal is to reduce preventable diseases, such as asthma and diabetes.[35]

Economic development

Brown led the administration’s economic development portfolio. He served as chair of numerous economic development initiatives, including the Joint Legislative and Executive Commission on Oversight of Public-Private Partnerships, the Governor’s Subcabinet on Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC), and the FastTrack initiative – part of Maryland Made Easy (www.easy.maryland.gov) – to streamline the state permitting process for businesses and developers.[36]

Public-private partnerships

Brown became one of the leading champions for the increased use of public-private partnerships to advance infrastructure projects in Maryland. Governor Martin O’Malley appointed Brown to serve as Chair of the Joint Legislative and Executive Commission on Oversight of Public-Private Partnerships. The fifteen-member Commission was established in 2010 under House Bill 1370 to evaluate the State’s framework and oversight of public–private partnerships. Under Brown’s leadership, the Commission worked to increase the potential for private investment in public infrastructure projects. The commission submitted its final report to the Governor and General Assembly in January 2012, which included assessing the oversight, best practices, and approval processes for public-private partnerships in other states; evaluating the definition of public-private partnerships; making recommendations concerning the appropriate manner of conducting legislative monitoring and oversight of public-private partnerships; and making recommendations concerning broad policy parameters within which public-private partnerships should be negotiated.[37]

Base realignment and closure (BRAC)

Brown was tasked by Governor O’Malley to lead the Base Realignment and Closure Subcabinet and the implementation of Maryland’s BRAC Plan, which ensured the State of Maryland would be ready for the 28,000 households that came to the state as a result of the BRAC process. It was estimated that between and 45,000 to 60,000 jobs would be created in Maryland by 2016 due to BRAC.[38] Since 2007, the BRAC Subcabinet met regularly with BRAC stakeholders to coordinate and synchronize the State’s efforts with public and private partners to address BRAC needs. The BRAC Plan set forth new initiatives and priorities to address the human capital and physical infrastructure requirements to support BRAC, as well as to seize the opportunities that BRAC presents, while preserving the quality of life already enjoyed by Marylanders. Several of the larger moves included the Army’s Communications–Electronics Command (CECOM) to Aberdeen Proving Ground from Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey, and the Air National Guard Readiness Center at Joint Base Andrews Naval Air Facility Washington. The Defense Information Systems Agency was relocating to Fort George G. Meade from northern Virginia and Walter Reed Army Medical Center was moving to the Bethesda Naval Hospital to create the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center at Bethesda.

In 2011, the Association of Defense Communities recognized Brown as their Public Official of the Year for his leadership on BRAC.[39]

Domestic violence

In August 2008, his cousin Kathy was murdered by her estranged boyfriend.[40] Building on his legislative experience and personal perspective, Brown has championed reforms to fight domestic violence and provide improved support to victims.

In 2009, Brown led efforts to improve domestic violence laws and take guns out of the hands of domestic abusers by allowing judges to order the abuser in a temporary protective order to surrender any firearms in their possession.[41]

During the 2010 Legislative Session, Brown worked with the General Assembly to pass legislation allowing a victim of domestic abuse to terminate a residential lease with a copy of a final protective order.[42] During the 2012 Legislative Session, Brown gained the administration’s goal of extending unemployment benefits to a victim of domestic violence who decides to leave employment because the abuser is a threat at the workplace.

Brown also led efforts to expand the availability of hospital-based Domestic Violence Screening programs at Maryland hospitals to help identify victims of domestic violence and connect them to support services. In 2010, he helped launch Maryland’s fifth hospital-based domestic violence program at Prince George’s Hospital Center in Cheverly. In 2011, Brown helped launch a sixth hospital-based program at Meritus Medical Center in Hagerstown, Maryland. Similar programs are in place in the Baltimore region at Anne Arundel Medical Center, Mercy Medical Center, Sinai Hospital, and Northwest Hospital.[43]

Education

Under the O’Malley Brown Administration, Maryland’s students made dramatic improvements in nearly every statistical category,[citation needed] and Maryland’s schools were ranked # 1 in the country for 4 years in a row.[44]

Brown lead the O’Malley-Brown administration’s efforts to increase taxes to support education and other programs. They raised taxes over 40 times during their tenure. The administration took steps to make a higher education more accessible and affordable for all Marylanders, including making record investments in community colleges and working to keep an education affordable at four-year public colleges and universities. As a result, the number of STEM college graduates, number of associate degrees, and the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded in Maryland all increased since the team took office in 2007.[44]

In 2010, Lt. Governor Brown launched the Skills2Compete initiative, which promotes programs and activities that lead to increasing the skill level of Marylanders though the attainment of a post-secondary credential, apprenticeship program or degree.[45]

Veterans affairs

Brown was the nation’s highest-ranking elected official to have served a tour of military duty in Iraq[4][5] and he led the O’Malley-Brown Administration’s work to improve benefits and services for Maryland’s veterans.[citation needed]

In 2012, Brown announced the launch of Maryland Homefront: the Veterans and Military Family Mortgage Program, which helps qualified current and former military members find homes by giving them a discounted mortgage interest rate and help with closing costs.[citation needed] Also in 2012, Brown helped pass legislation that allows notation of ‘veteran’ status on drivers’ licenses and identification card.[citation needed]

During the 2008 session of the Maryland General Assembly, Brown led the administration’s successful efforts to pass a sweeping veterans package, including passage of the Veterans Behavioral Health Act of 2008. The legislation sets aside $2.3 million for the expansion of direct services to OIF/OEF veterans living with behavioral and mental health problem. The legislation also named Brown chair of the Maryland Veterans Behavioral Health Advisory Board.[46][47]

Other legislation passed as part of the “Maryland’s Commitment to Veterans” package includes:

- Expansion of state scholarship fund for OIF/OEF veterans and their dependents;

- Protection of state-funded business loan program for veterans and service-disable veterans;

- Creation of reintegration program for members of the Maryland National Guard returning from service in Iraq and Afghanistan; and

- Expansion of state veteran service centers in rural communities.

2008 election and Obama transition

Despite being a classmate of Barack Obama, in September 2007, Brown initially endorsed Hillary Clinton for President in the 2008 election.[48][49] He campaigned for her in several states, including South Carolina and Georgia.[50] In June 2008, Brown subsequently endorsed Obama.

In July 2008, Brown was appointed to the Democratic National Committee‘s Platform Committee and served on the Platform Drafting Committee. Brown led the efforts to strengthen the Democratic Party‘s commitment to veterans and ensuring that the Chesapeake Bay be named as a “national treasure”.[51] Brown was a “Party Leader/Elected Official” delegate to the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado, in late August 2008 and cast his vote for then-Senator Obama, along with 98 members of the Maryland delegation.[52]

Brown was named co-chair of the Obama/Biden Presidential Transition Agency Review Team for the Department of Veterans Affairs on November 14, 2008.[53]

2014 gubernatorial candidacy

Anthony Brown announced his candidacy for governor of Maryland in the 2014 election on May 10, 2013, at Prince George’s County Community College. He chose Ken Ulman, county executive of Howard County, Maryland, as his running mate in June 2013.[54] Brown was endorsed by Governor Martin O’Malley, U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski, U.S. Congressman Steny Hoyer, Maryland Senate President Thomas V. Miller Jr., and Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. Brown faced Attorney General Doug Gansler and Delegate Heather Mizeur in the Democratic primary.[55] Brown won the June 2014 Democratic primary[56] and became the Democratic nominee for governor but was defeated by Republican nominee Larry Hogan in the general election on November 4, 2014.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Larry Hogan | 847,280 | 51.45% | +9.66% | |

| Democratic | Anthony Brown | 771,242 | 46.83% | −9.41% | |

| Libertarian | Shawn Quinn | 23,813 | 1.44% | +0.68% | |

| Write-ins | 4,265 | 0.25% | |||

| Turnout | 1,655,375 | 45%[57] | |||

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

- 2016

On March 12, 2015, The Baltimore Sun reported that Brown would run for the U.S. House of Representatives seat for Maryland’s 4th district, which was being vacated by Donna Edwards, who was running for the US Senate.[58] He won a crowded six-way Democratic primary—the real contest in this heavily Democratic, black-majority district—with 41 percent of the vote.[59]

Brown won the seat in the general election, taking over 73 percent of the vote.[60]

Tenure

Committee assignments

- Committee on Armed Services (Vice Chair, 2017–2021)

- Committee on Ethics

- Committee on Natural Resources

- Committee on Transportation & Infrastructure

Caucus memberships

- Congressional Black Caucus[61]

- New Democrat Coalition[62]

- Medicare for All Caucus[63]

- Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus[64]

- U.S.-Japan Caucus[65]

- Blue Collar Caucus[1]

Attorney General of Maryland

Elections

- 2022

Brown said that he would not seek re-election to the House of Representatives on October 25, 2021, instead announcing that he would run for Attorney General of Maryland.[8]

During the primary, Brown received endorsements from U.S. Senators Cory Booker[66] and Elizabeth Warren,[67] and U.S. Representatives Steny Hoyer,[68] Kweisi Mfume, and David Trone.[69] He also received endorsements from the Maryland Sierra Club[70] and the Maryland State Education Association.[71]

In May 2022, an investigation from Time alleged that Brown violated state election laws by using funds from his congressional campaign account to bankroll his bid for attorney general.[72]

Brown won the Democratic primary election on July 19, 2022, defeating former First Lady of Maryland Katie O’Malley with 55.1 percent of the vote.[73] He defeated Republican lawyer Michael Peroutka in the general election on November 8, 2022.[9]

Tenure

Brown was sworn in on January 3, 2023, becoming Maryland’s first Black attorney general.[74][75]

Before Brown took office in 2023, the Maryland Attorney General’s office launched an investigation into allegations of sexual abuse perpetrated by members of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Baltimore.[76][77] Brown inherited the investigation, and, in April 2023, released a 463-page report accusing the Archdiocese of covering up more than 600 cases of child sexual abuse against 156 Catholic priests over 80 years.[78] Following its release, he said that the Attorney General’s office had ongoing investigations into sexual abuse allegations in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wilmington.[79]

In January 2023, ahead of his swearing in, Brown said he supported legislation that would allow him to sue companies and individuals for civil rights violations.[80] He also set out multiple goals for his time in office, including increasing salaries and employment in the Attorney General’s office, enforcing environmental regulations,[81] and investigating police misconduct.[82] The Maryland General Assembly passed bills during its 2023 legislative session that gave the Attorney General’s office the authority to prosecute police-involved deaths and civil rights violations in housing and employment,[83] which were signed into law in May 2023.[84]

Brown was an at-large delegate to the 2024 Democratic National Convention, pledged to Kamala Harris.[85] During the second presidency of Donald Trump, he filed numerous lawsuits against the Trump administration.[86][87]

Personal life

Brown married Patricia Arzuaga in 1993, and they had two children, Rebecca and Jonathan, before their divorce in 2009.[88] Jonathan was adopted.[89]

Brown married Karmen Walker on May 27, 2012. She is the widow of Prince George’s County police officer Anthony Michael Walker. He became the stepfather of Walker’s son Anthony.[88][90][91] Both Anthony and Brown’s son Jonathan were in the same grade at the same Catholic school in 2012.[91] Walker is a director of government relations with Comcast.[88][92] Brown is Catholic.[93]

Awards, ribbons, and badges

Brown’s personal awards include:[1]

| 1st row | Legion of Merit | Bronze Star Medal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd row | Meritorious Service Medal | Army Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters | Army Achievement Medal with one oak leaf cluster |

| 3rd row | Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal with four oak leaf clusters | National Defense Service Medal with bronze service star | Iraq Campaign Medal |

| 4th row | Global War on Terrorism Service Medal | Outstanding Volunteer Service Medal | Armed Forces Reserve Medal with Hourglass (not shown) and “M” devices |

| 5th row | Army Service Ribbon | Army Overseas Service Ribbon | Army Reserve Overseas Training Ribbon with award numeral 2 |

Brown was also awarded the Army Aviator Badge, and the Army Superior Unit Award. He is Airborne and Air Assault qualified, and is authorized to wear one Overseas Service Bar.

See also

- List of African-American United States representatives

- List of minority governors and lieutenant governors in the United States

References

- ^ a b c d “Anthony G. Brown, Lt. Governor Archived April 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine“. Political biography. Maryland State Archives . Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ “O’Malley/Brown in Maryland gubernatorial race[permanent dead link]“. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 10, 2007. Not available online as of January 13, 2007.

- ^ “Maryland election results 2010: Martin O’Malley beats Bob Ehrlich in a rematch for Governor”. The Washington Post. November 2, 2010. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Shoop, Tom (November 21, 2008). “Maryland Lt. Gov. ‘Serious’ Contender for VA Slot”. National Journal. Archived from the original on January 12, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

having spent 10 months in the country in 2004

- ^ a b Bush, Matt (May 23, 2012). “Fundraising Website Launched By Maryland Lt. Gov. Brown”. wamu.org. American University. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ “Republican Larry Hogan wins Md. governor’s race in stunning upset”. washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ “Maryland U.S. House 4th District Results: Anthony Brown Wins”. The New York Times. August 1, 2017. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Wilson, Reid (October 25, 2021). “Rep. Brown to run for Maryland attorney general”. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Mann, Alex (November 8, 2022). “Democratic U.S. Rep. Anthony Brown claims victory in Maryland attorney general race; early returns show sizeable lead over Republican Michael Peroutka”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ “Roy Hershel Brown Obituary”. The New York Times. February 3, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015 – via Legacy.com.

- ^ Montgomery, David (October 28, 2006). “A Demanding Race”. The Washington Post. p. C1. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ “One to watch: Maryland’s Lt. Governor Anthony Brown”. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Cox, Erin (October 18, 2014). “Brown on a deliberate march toward goal years in the making”. baltimoresun.com. Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ “Md. Lawmaker Trades Politics For New Fight (washingtonpost.com)”. Wp-dr.wpni.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ This is the official formatting of the brigade and division names, per“Lineage And Honors Information”. United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ “Obama pays tribute to NAACP’s John Payton”. Politico.Com. March 19, 2012. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Wagner, John (April 21, 2014). “Brown updates state biography to include work with wealth-management firm in 1999”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Wagner, John (May 17, 2014). “For Maryland Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown’s campaign, service has become central”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ Cook, Dave. “O’Malley Picks Anthony Brown as Running Mate Archived December 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine“. Baltimore Times. December 16, 2005. from Martin O’Malley political website. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ “Martin O’Malley News and Photos”. baltimoresun.com. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ “2010–2011 Officers & Executive Committee”. nlga.us. National Lieutenant Governors Association. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ “Lt. Governor Anthony Brown Completes Term as Chair of National Lieutenant Governors Association”. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ “Lt. Governor Brown Receives Public Health Hero Award” (Press release). Office of Lt. Governor Anthony Brown. June 7, 2012. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ “Maryland Health Care Reform Simulation Model: Detailed Analysis and Methodology” (PDF). The Hilltop Institute. July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ “Health Care Reform Simulation Model Projections” (PDF). The Hilltop Institute. July 13, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Press Release. “O’Malley-Brown Administration’s Health Care Reform Package Signed Into Law Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. April 12, 2011. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ McCartney, Robert (December 11, 2013). “Brown bungles health-care plan debut but will probably win Md. governorship anyway”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ “Md. spent $90 million on health exchange technology, according to cost breakdown”. The Washington Post. April 14, 2014. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ WBALTV11 (January 15, 2014). “O’Malley administration apologizes for botched health exchange rollout”. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Johnson, Jenna; Flaherty, Mary Pat (March 30, 2014). “Maryland gears up for health exchange redo”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Jenna; Flaherty, Mary Pat (February 27, 2014), “Maryland begins to put a price on health-care exchange debacle”, The Washington Post, archived from the original on March 2, 2014, retrieved March 10, 2014

- ^ Gantz, Sarah (March 10, 2014). “Feds to investigate Maryland’s health exchange”. Baltimore Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ “Obamacare rule eased for states with website troubles”. CBS News. Associated Press. February 28, 2014. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ “Senate Bill 234”. Maryland General Assembly. 2012. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ “What is a HEZ?”. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Press Release. “Lt. Governor Brown Testifies Before General Assembly on Job Creation Through Infrastructure Projects Archived November 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. October 18, 2011. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ Press Release. “Lt. Governor Brown Presides Over Joint Legislative and Executive Commission on Oversight of Public-Private Partnerships Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. August 31, 2011. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ “Base Realignment and Closure Study Assesses Impact on Maryland Resources” (Press release). Office of the Lt. Governor. February 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ “Maryland’s Lieutenant Governor Earns Defense Community Award” (Press release). Association of Defense Communities. July 7, 2011. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ News Article. “Maryland Receives $2M Grant To Stop Domestic Violence Archived April 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine“. WAMU 88.5 American University Radio. October 31, 2011. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ Press Release. “Statement from Lt. Governor Anthony G. Brown on Passage of HB 296 and HB 302 Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. March 17, 2009. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ Press Release. “Lt. Governor Brown Applauds Delegate Glenn, General Assembly for Passing Strong Legislation to Protect Victims of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Archived December 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. April 9, 2010. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ Press Release. “Lt. Governor Brown Announces New Hospital-Based Domestic Violence Program at Prince George’s Hospital Center Archived December 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. October 20, 2010. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ a b “Governor O’Malley’s 15 Strategic Policy Goals: 2. Improve Student Achievement and School, College, and Career Readiness in Maryland by 25% by End 2015”. Office of Governor Martin O’Malley. January 12, 2012. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ Press Release. “Lt. Governor Brown Tours New Dorchester Career & Technology Center Archived December 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine“. Office of Lt. Governor. June 29, 2011. From Lt. Governor Brown’s official website. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- ^ Bowman, Joshua (September 24, 2008). “Md.’s lieutenant governor promotes veterans program during Boonsboro visit”. The Herald-Mail. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ “Lt. Governor Anthony Brown and the Maryland Higher Education Commission Launch New Veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq Conflicts Scholarship Program”. Office of the Lt. Governor. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ “Hillary Clinton: Press Release – Maryland Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown Endorses Clinton”. Presidency.ucsb.edu. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ “Lt. Gov. Anthony G. Brown, Maryland, Former Obama Classmate, Endorses Clinton – Democratic Underground”. Upload.democraticunderground.com. September 24, 2007. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ “O’Malley’s Clinton ties get politically thorny”. The Baltimore Sun. February 8, 2008. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ “Lt. Governor Anthony G. Brown Named to Democratic National Committee Platform Drafting Committee”. Office of the Lt. Governor of Maryland. July 8, 2008. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ “Political Parties”. Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ Dechter, Gadi (November 18, 2008). “Lt. Gov. Brown a co-chair of Obama veterans team”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ Cox, Erin (June 3, 2013). “Brown names Ulman as his running mate”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Wagner, John (September 17, 2013). “Brown plans to announce Mikulski’s endorsement at campaign event Sunday”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ Shepard, Steven (June 24, 2014). “Democrat Anthony Brown wins Maryland governor primary”. Politico. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ Sandoval, Timothy (November 5, 2014). “Low Democratic turnout propelled Larry Hogan to victory in Maryland governor’s race”. Baltimore Business Journal. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ Fritze, John (March 12, 2015). “Anthony Brown to run for House seat”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ “Official 2016 Primary Election Results”. Maryland Secretary of State. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ “Unofficial 2016 Presidential General Election results for Representative in Congress – District 4”. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Black Caucus. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ “Members”. New Democrat Coalition. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ “Committees and Caucuses”. Anthony Brown. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ “Members”. U.S. – Japan Caucus. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle; Kurtz, Josh (June 30, 2022). “Political Notes: Billionaire Drops $500K to Oust Elrich, Sierra Club Corrects the Record, AG and Dist. 6 News”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Cox, Erin (April 8, 2022). “Elizabeth Warren endorses Anthony Brown in Md. attorney general race”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ DePuyt, Bruce (December 2, 2021). “Hoyer Endorses Brown for Attorney General”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ DePuyt, Bruce (October 30, 2021). “Trone, Mfume Endorse Brown for Maryland Attorney General”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Gaskill, Hannah; Kurtz, Josh; Peck, Louis (May 27, 2022). “Political Notes: Booker Rallies Md. Dems, Adams on the Air, and News About Endorsements”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E. (April 2, 2022). “Wes Moore Nabs Coveted State Teachers’ Union Endorsement”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Cortellessa, Eric (May 9, 2022). “Exclusive: U.S. Congressman’s Campaign May Violate State Election Law”. Time. Archived from the original on July 20, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Bradner, Eric; Shelton, Shania (July 19, 2022). “CNN projects Trump-backed Dan Cox will win GOP gubernatorial primary in Maryland”. CNN. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ “Maryland’s first Black attorney general Anthony Brown to be sworn in Tuesday”. WJLA-TV. January 3, 2023. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Prudente, Tim (January 3, 2023). “Anthony Brown takes oath as Maryland’s first Black attorney general”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ DePuyt, Bruce (February 27, 2019). “Frosh Taps Elizabeth Embry to Probe Sex Abuse Allegations in Baltimore Archdiocese”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Bowie, Liz; Prudente, Tim (November 17, 2022). “Maryland AG’s investigation of ‘pervasive’ Catholic Church abuse documents 158 priests, more than 600 victims”. The Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ “Report details ‘staggering’ church sex abuse in Maryland”. AP NEWS. April 5, 2023. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ Segelbaum, Dylan (April 5, 2023). “Investigations of Archdiocese of Washington, Diocese of Wilmington are ongoing, Maryland AG says”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Wiggins, Ovetta (January 2, 2023). “Md. attorney general-elect wants power to sue civil rights violators”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Sanderlin, Lee O. (January 2, 2023). “Maryland Attorney General-elect Anthony Brown’s goals and priorities in his own words”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Segelbaum, Dylan (January 2, 2023). “Maryland Attorney General-elect Anthony Brown on his priorities in office”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ O’Neill, Madeleine (April 11, 2023). “Lawmakers grant new powers to Maryland Attorney General’s Office”. The Daily Record. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (May 16, 2023). “Maryland Gov. Wes Moore to sign laws restricting who can carry firearms and where they can carry them”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (July 22, 2024). “Meet the Maryland delegates to the Democratic National Convention”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Wintrode, Brenda; O’Neill, Madeleine (February 1, 2025). “Maryland’s AG is building a million-dollar litigation team to battle Trump”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved July 2, 2025.

- ^ O’Neill, Madeleine (February 14, 2025). “Lawsuit tracker: How Maryland, Baltimore are suing the Trump administration”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved July 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c “Md. Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown Announces Engagement”. CBS Baltimore. Associated Press. May 16, 2011. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Anthony G. (November 26, 2012). “Anthony Brown: My Son Jonathan”. Glen Burnie Patch. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ “Maryland Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown marries Karmen Bailey Walker in College Park”. The Washington Post. May 30, 2012. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ a b “A ‘little hug thing’ blossoms in Md”. The Washington Post. May 30, 2012. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

Walker’s son Anthony, 12, is a few months older than Brown’s son Jonathan, and the two are in the same grade at the same Catholic school.

- ^ “Maryland Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown is engaged”. The Washington Post. May 16, 2011. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ Murphy, Caryle (March 24, 2006). “Cardinals Scramble To Defeat Abuse Bills; Child Victims Would Get More Time to Sue in Md”. The Washington Post. via HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

Committee member Anthony G. Brown (D-Prince George’s), who is Catholic

External links

- Congressman Anthony Brown Archived January 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine official U.S. House website

- Campaign website

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN

Issues

Source: Government page

Committees

The House of Representatives has 20 standing committees which have jurisdiction over specific issue areas. These committees play an important role in the legislative process, hold hearings and oversee agencies and programs within their purview.

Congressman Brown has been appointed to the follow committees for the 116th Congress:

House Armed Services Committee

The Armed Services Committee is responsible for policy related to defense policy generally; ongoing military operations; the organization and reform of the Department of Defense and national security functions of the Department of Energy; and consideration of the annual defense authorization and budget that involves millions of military and civilian personnel, thousands of facilities, and hundreds of agencies, departments and commands throughout the world.

Subcommittee Assignments:

Seapower and Projection Forces

Tactical Air & Land Forces

House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

The House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure has jurisdiction over all modes of transportation: aviation, maritime and waterborne transportation, highways, bridges, mass transit, and railroads. The Committee also has jurisdiction over other aspects of our national infrastructure, such as clean water and waste water management, the transport of resources by pipeline, flood damage reduction, the management of federally owned real estate and public buildings, the development of economically depressed rural and urban areas, disaster preparedness and response, and hazardous materials transportation.

In addition, the Transportation Committee has broad jurisdiction over the Department of Transportation, ,the U.S. Coast Guard, Amtrak, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Economic Development Administration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and others. The Committee also has jurisdiction over federal buildings, which includes the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Subcommittee Assignments:

Highways and Transit

Aviation

Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation

House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

The House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs has jurisdiction over veterans’ measures generally, including veterans’ hospitals, medical care, treatment compensation, vocational rehabilitation, and education, as well as over pensions of all the wars of the United States (general and special), the readjustment of servicemembers to civil life, and servicemembers’ civil relief. To ensure veterans receive these crucial services and benefits, the Committee is committed to its oversight role of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, including the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and the National Cemetery Administration (NCA). The Committee also oversees life insurance issued by the Government on account of service in the Armed Forces as well as the cemeteries of the United States in which veterans of any war or conflict are or may be buried (whether in the United States or abroad, except cemeteries administered by the Secretary of the Interior).

Subcommittee Assignments:

Economic Opportunity

Technology Modernization

Legislation

You can also learn more about legislation sponsored and co-sponsored by Congressman Brown. You can also view Congressman Brown’s vote record here.

Issues